As an architecture student at Waseda University in the late 90s Kyohei Sakaguchi encountered a structure that would forever shape his future career. It wasn’t Oscar Niemeyer’s Brazilian National Museum, nor was it Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation. Not even Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower. It was a home built on a budget of zero yen on the bed of Tokyo’s Sumida River.

“Zero Yen House” (Sumida River, Tokyo)

“Zero Yen House” (Sumida River, Tokyo)

Suzuki-san inside his Zero Yen House

Suzuki-san inside his Zero Yen House

The owners at the time, 59-year old Suzuki-san and 52-year old Mi-chan, moved to Tokyo from Fukushima and built their palace with found materials. They live off money they got for recycling aluminum cans, and from spare electricity leftover from discarded car batteries. (Did you know that “dead” car batteries can power a small TV for 10 days at 5 hours of usage a day!?). “But I don’t call them ‘homeless,’” says Sakaguchi, of his revelation. “They have a house. I rent a house.”

“A House with a Slide” (Nagoya) built around an abandoned children’s playground

“A House with a Slide” (Nagoya) built around an abandoned children’s playground

“A Japanese restaurant” (Nagoya)

“A Japanese restaurant” (Nagoya)

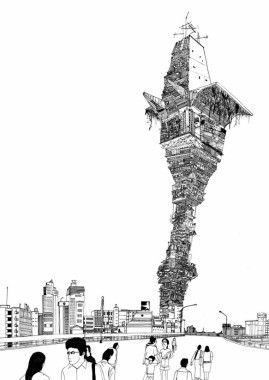

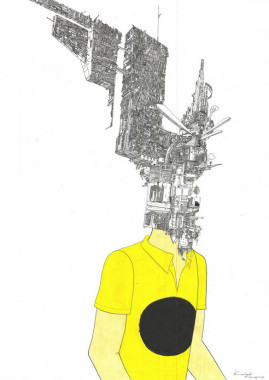

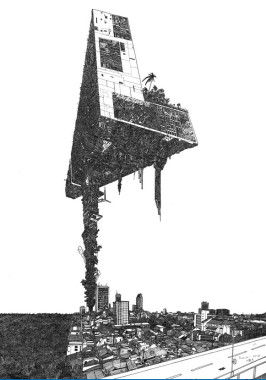

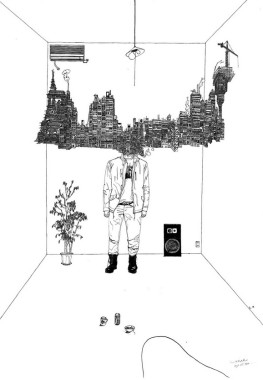

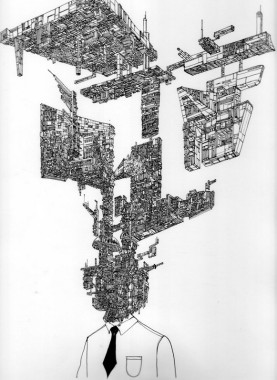

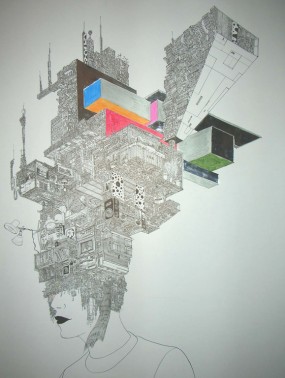

Sakaguchi began documenting the many Zero Yen Houses he found. He would interview inhabitants in order to gain a deeper understanding to their way of life. He grappled with the idea of land and property and the fallacy, he believed, of how we are told we have to own land before we can build a house on it. He struggled with notions of urbanity, and how cities clash with their natural surroundings, swallowing up the residents. This eventually led to a series of dream-like prints called “Dig-ital” that portrayed a dystopian cityscape of unbalanced buildings that expand out like a jungle.

“Dig-ital” (2006 ~ ) by Kyohei Sakaguchi | click to enlarge

As fate would have it, Fukushima – where Suzuki-san was originally from – delivers to Sakaguchi another jolt, this time in a less amiable form. The Tohoku earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011 cripples the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Reactor, which begins spewing radiation into the atmosphere. Concerned about health-impacts on his 2-year old daughter, Sakaguchi relocates to Kumamoto, his hometown in Southern Japan. It is here that he comes across an abandoned 80-year old home and decides to build his very own Zero Yen House. On May 16, 2011 he opened “Zero Center,” a refugee camp for those affected by the nuclear fallout. Twitter became a powerful tool for Sakaguchi, who used the social networking service to spread the word about his new camp.

The response was overwhelming. About 30 or 40 people brought their families and relocated to the Zero Center, which continues to function as a self-sustaining bohemian society. Sakaguchi eventually wants to transform Kuamoto into and “arts capital” – a place where people can live off of art. Architecture is governed by building codes and regulations, he says, but art and all its blank space is autonomous. That is where I sense the greatest potential.

The work of Kyohei Sakaguchi is currently the subject of an exhibition at Watari-Um, which runs through February 3, 2013.