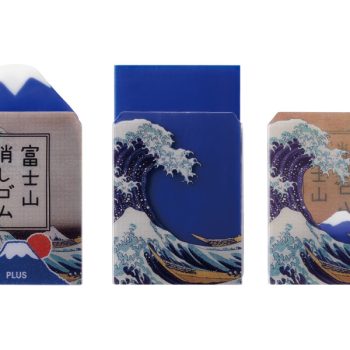

“Nakamura Shikan as Denshichi.” Toyokuni III. Woodblock Print. 14” x 9.5.”1861.

“Tattoos are complicated cultural symbols, simultaneously representing both belonging and non-conformity.” And in Japan they are all the more complex. In a rather lengthy post a while back we wrote about how tattoos were first uses as a form of punishment in Japan.

However, criminals began covering their penal tattoos with decorative ones rendering the punishment obsolete. This is thought to be the historical origin of the association of tattooing and organized crime in Japan.

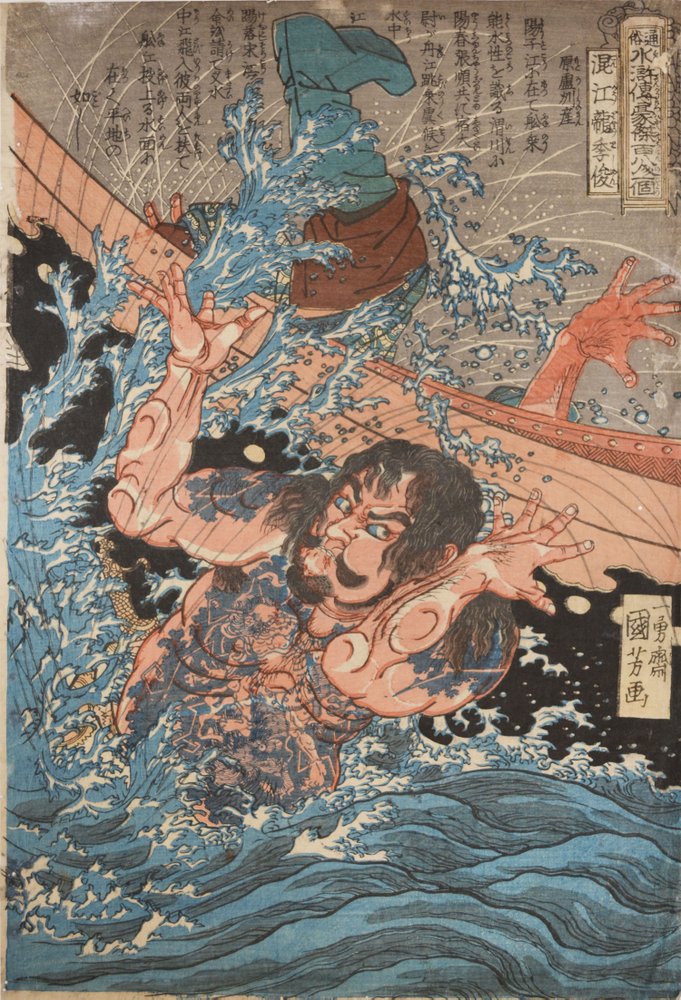

In the early 18th century pictorial tattooing begins to flourish due, in part, to the development of ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) and the needs of popular culture in Edo. Irezumi (literally, the insertion of ink) “and printmaking became deeply referential, sharing themes and styles on paper and skin,” notes the Ronin Gallery in New York. In an upcoming exhibition titled “Taboo: Ukiyo-e & The Japanese Tattoo Tradition” the midtown Manhattan gallery plans to showcase the enduring conversation between ukiyo-e and irezumi.

“Ichikawa Danjuro as Kyumonryu Shishin.” Kunichika Woodblock Print. 14” x 9.5.”1898.

The works of print masters like Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi, and Kunichika will be juxtaposed with contemporary interpretations of the tradition from work by Horiyoshi III (an acclaimed tattoo artist), photographer Masato Sudo and Kyoto-based American artist Daniel Kelly.

There is an opening reception on March 5 from 5:30pm but the exhibition itself runs through April 30, 2015.

“Kyumonryu Shishin from the Heroes of the Suikoden.” Yoshitoshi. Woodblock print. 13.75” x 9.25.” 1868.

“Konkoryu Rishun from the Heroes of the Suikoden.” Kuniyoshi. Woodblock Print.15” x 10.” c.1830.

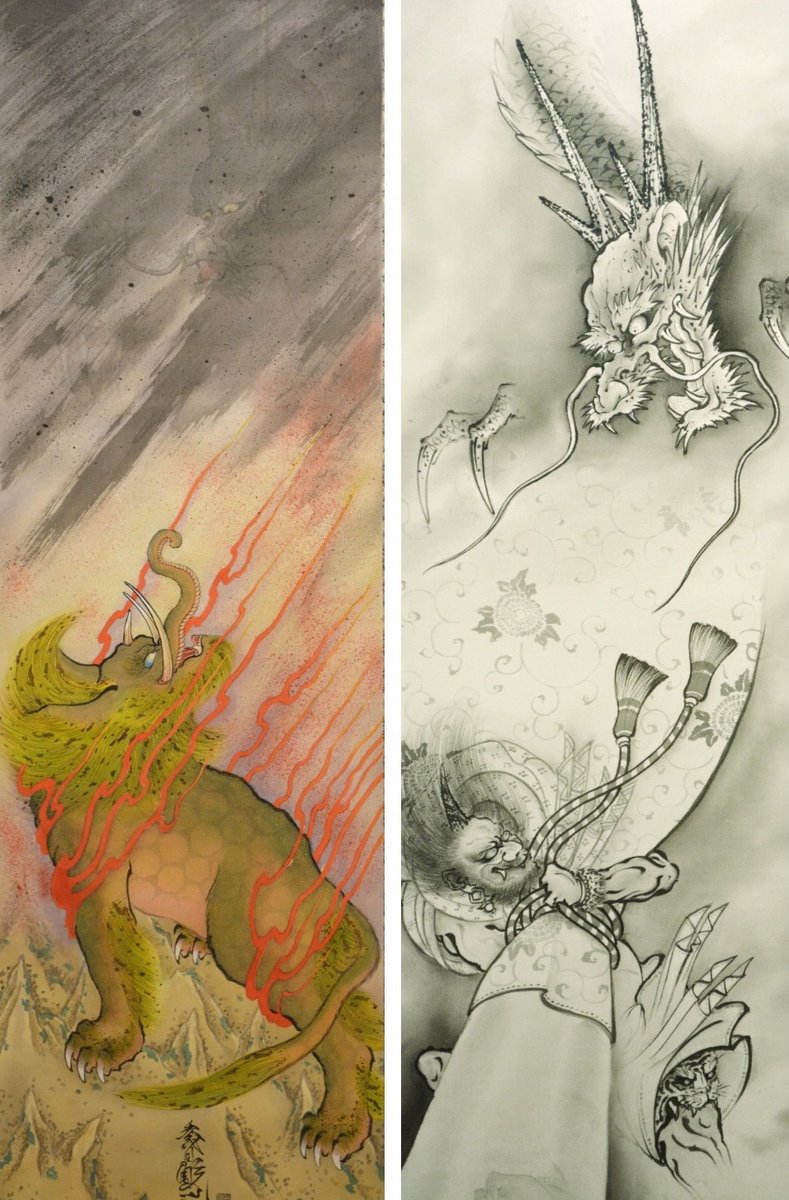

“Baku” (left) and “Fujin and Raijin” (right) by Horiyoshi III.