Ask Japanese friends what their family crest is and most likely they will be able to tell you. Crests (kamon or mon in Japanese) are still in use today. But while many Japanese know their family’s crest, not many own an item with their crest on it.

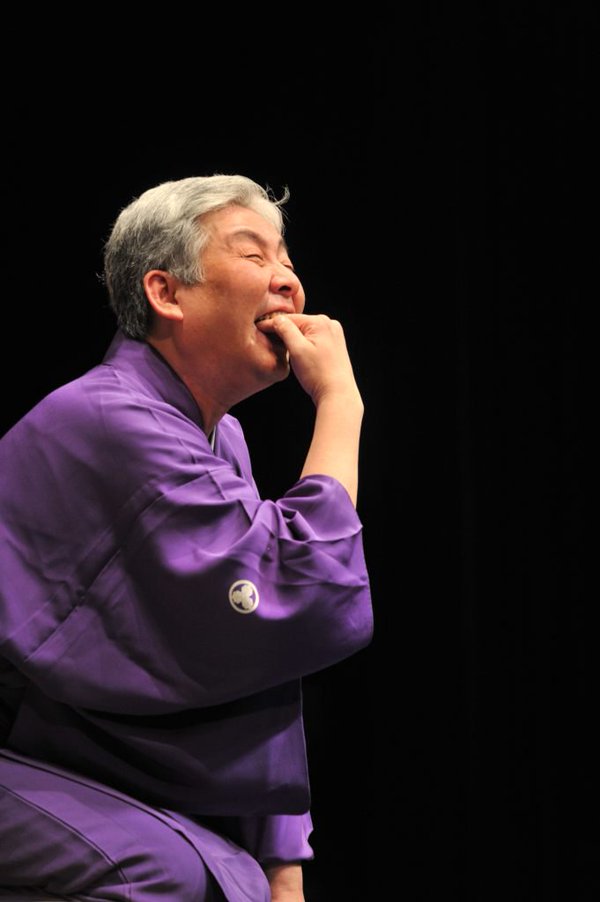

All in all, crests are no longer present in daily life. The only time you’re likely to see a mon is when attending a Japanese wedding – men wear formal kimono called montsuki (“with crest”). Or go to a Rakugo performance – actors will wear kimono with their master’s crest.

Master Kyotaro during a performance of “Nedoko” in Tokyo (April 2016). On his kimono, the family crest Maru ni mitsu kashiwa (“Three oak leaves in a circle”). Photo by Tachibana Renji.

A wide range of motifs can be found on mon, mostly taken from nature: animals, birds or plants. In medieval Europe, only nobility was allowed to bear coat of arms. Things were a bit different in 16th century Japan where only samurai were allowed to have surnames – a crest was a way to distinguish yourself from others, distinguish your shop, your brand. Even people at the bottom of society, such as vaudeville actors or courtesans had their own mon.

Untitled ukiyoe by Kitagawa Utamaro (1795) of a woman, also with the Maru ni mitsu kashiwa

Sometime in the Muromachi period (1336 – 1573) when samurai started to wear their family crest the profession of monshō-uwa-eshi was born: Craftsmen who paint mon onto kimonos. Since they painted mostly on request by textile merchants or kimono shops – only trading business-to-business, the profession was not widely known.

Hatoba Shoryu, a 3rd generation monsho-uwa-eshi, says that today there are 50,000 different mon. He is one of the few remaining monshō-uwa-eshi who do not only paint but also design crests. As they are no longer widely used, rather than sticking to his trade and painting only mon on kimono, he ventures out and actively seeks to collaborate with artists, artisans and even brands of all different genres.

Hatoba Shoryu and his son Yoji in front of badges showing many of their mon designs

Recently he designed traditional noren curtains hanging in front of the COREDO shopping complex’s electronic sliding doors in Nihonbashi. He also recently collaborated with the Kleenex brand on a high-end line of tissues.

Cherry Blossom crest in front of the Coredo Muromachi 3 department store in Nihonbashi

The Kinran box of tissues

Originally monsho-uwa-eshi used bun-mawashi: bamboo compasses to draw the mon. But thanks, in part, to the son, Hatoba Shoryu recently began incorporating Adobe Illustrator into his process. In the first part of this short video produced for Design A,an NHK children’s program, you can see the traditional bun-mawashi method – soon followed by an example of how Illustrator helps him to design new mon today.

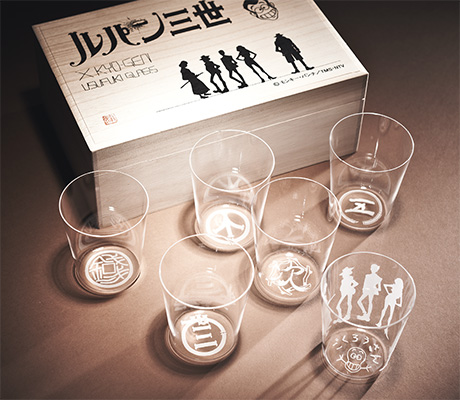

For the 50th anniversary of the popular anime Lupin the Third, the department store Isetan asked Hatoba Shoryu to design mon for the characters of the anime and turn them into a series of drinking glasses and badges. Each design incorporates typical items for the characters: the mon for Lupin the Third, the master thief, includes the two Kanji for “the Third”. The first kanji of his adversary’s name, Inspector Zenigata, (zeni specifically refers to a “round coin with a square hole in the center”) has become Inspector Zenigata’s mon.

Today, Hatoba Shoryu also takes in requests from abroad – shops or individuals who want their own family crest provide him with specifications – on engraved in glasses, on kimonos or if you have an extra million Yen at hand, on a chest of drawers.

a chest of drawers created in collaboration with a Japanese interior designer